I need to change the format of this blog. The last few posts have been monsters of thousands of words each. What I thought I could finish in a few days has taken several months. I just don't have the time to continue on at this pace. My computer is slowly seizing up, and in any case I don't know how many people are reading these beasts to the end. I am surprised and delighted to find that a few are taking the time to slog it through.

So I've got to try a new model for writing. At least for now. There are a few more huge rants I need to get out, but they can wait for a while. The new model comes from Ezra Pound. Pound has a lot to say about writing in general that is extremely helpful. Writing, he repeatedly stresses, should present images in the clearest, most concise way possible. Sentences should be packed with meaning and all superfluous words should be eliminated. Writing should shine.

becoming Leaf becoming Coal becoming Light

Pound also applies this clarity and precision to the subjects of poetry. Unlike usual prose, and especially writing on history, which presents general theories and a flurry of facts and impersonal trivia, poetry and good prose should explore specific details that are both meaningful to the author and throw light on the core of the subject at hand. These are what Pound calls "luminous details." He defined the term very precisely in 1912:

Any fact is, in a sense, 'significant.' Any fact may be 'symptomatic,' but certain facts give one a sudden insight into circumjacent conditions into their causes, their effects, into sequence, and law.

The Cantos are constructed of inter-reflecting luminous details. Pound's epic concerns itself with only those potent snippets of history that allow a slight glimpse behind the curtain. These "facts" provide "sudden insight" on the deeper tissues and processes of political, economic, social and transcendent reality. Pound scholar, Hugh Kenner, describes luminous details as "patterned integrities," comparing them with the self-emergent patternings of matter and energy.

Luminous Details, then, are "patterned integrities" which transferred out of their context of origin retain their power to enlighten us. They have this power because, as men came to understand early in the 20th Century, all realities whatever are patterned energies. If mass is energy (Einstein), then all matter exemplifies knottings, the self-interference inhibiting radiant expansion at the speed of light. Like a slip-knot, a radioactive substance expends itself. Elsewhere patterns weave, unweave, reweave: light becomes leaf becomes coal becomes light. [The Pound Era, my italics]

This taken alone is mind-blowing. The "knottings" of our own perception resound with the self-weaving pulses and patterns of nature. This resonance is also luminous. The tapestry is woven with threads of light. The medium of these patterns is secondary. They occur in thoughts, in written and spoken words, within organisms, in technology, in water, wind and rock. Pound, though, continually digs deeper. He also calls the luminous details, "barbs of time." This phrase, as Carroll F. Terrell suggests in The Companion to The Cantos of Ezra Pound, may have originated with Giordano Bruno:

barb of time: Perhaps an allusion to Giordano Bruno's motto vincit instans ("the instant triumphs"), of which Bruno says that the creative instant or inspiration is a barb of light which pierces the mind to give one a totally new perception beyond all mere logic chopping. This links up with Pound's notions regarding the "luminous detail."

The luminous detail, then, is both the instant of creative inspiration and the radiant recording of this instant. The two become indistinguishable. This is not at all logical, but it provides a "totally new perception." William Blake immediately comes to mind here and it is really no wonder that he arrived at an almost identical concept. Blake calls it the "Minute Particular." He writes of this often in Jerusalem.

Every Minute Particular is Holy

Blake means "holy" in the profoundly religious sense. The particular moment, a particular detail, is the one doorway to the eternal. The eternal is only revealed through particulars. It cannot be approached with generalities, or abstractions, or averages. Science fails to locate it in this regard. It shines through in the unique and the singular.

so he who wishes to see a Vision; a perfect Whole

Must see it in its Minute Particulars...

But General Forms have their vitality in Particulars: & every

Particular is a Man; a Divine Member of the Divine Jesus.

The religious terminology of "Divine Jesus" should not scare us off. Blake is explaining that the universe is personal and intimate, not abstract and indifferent. It is equivalent to the clearest expressions of our imagination and our highest apprehensions of beauty. Bruno may have been an influence on Blake here but it is obvious that the two, along with Pound, are writing about almost identical things.

Holes In The Tent

But how does the moment of perceiving a luminous detail happen? When exactly does the instant triumph? James Joyce lucidly lays out this process in his theory of aesthetics provided in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Stephen Hero. I've written about Joyce's theory elsewhere, but one quote from A Portrait offers new insights to this discussion:

The radiance of which he [Aquinas] speaks is the scholastic quidditas, the whatness of a thing. The supreme quality is felt by the artist when the esthetic image is first conceived in his imagination. The mind in that mysterious instant Shelley likened beautifully to a fading coal. The instant wherein that supreme quality of beauty, the clear radiance of the esthetic image, is apprehended luminously by the mind which has been arrested by its wholeness and fascinated by its harmony is the luminous silent stasis of esthetic pleasure...

As in Pound, Bruno and Blake, Joyce describes the instant apprehension of luminosity radiating out from the heart of each thing and uniting with the effulgent imagination of the artist. Art needs to be judged by how closely it portrays and even reenacts this instant. This moment is further called by Joyce, an "epiphany." Dubliners presents a series of epiphanies, Ulysses is a epiphany stretched out to a single day, and Finnegans Wake is all of history epiphanized.

Percy Bysshe Shelley's image of the "fading coal" also deserves some looking into. Joyce finds this image in Shelley's essay "A Defence of Poetry." In this essay Shelley, like Bruno, emphasizes that these moments cannot be brought on by reason or logic. The fading coal sparks once again to life with a sudden and unexpected gust of wind or inspiration, an "invisible influence."

Poetry is not like reasoning, a power to be exerted according to the determination of the will. A man cannot say, “I will compose poetry.” The greatest poet even cannot say it; for the mind in creation is as a fading coal, which some invisible influence, like an inconstant wind, awakens to transitory brightness; this power arises from within, like the color of a flower which fades and changes as it is developed, and the conscious portions of our natures are unprophetic either of its approach or its departure.

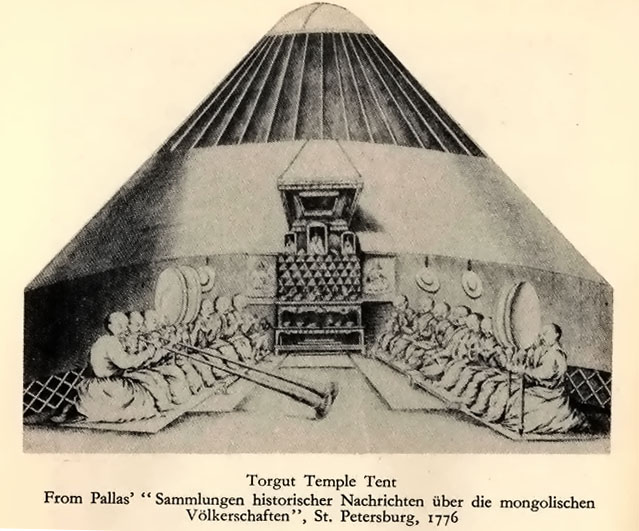

Shelley's vision is clearly shared. All of these poets are being struck with the same beams of light. The luminous details are constellated. As in Turko-Tartar mythology the firmament is the skin of a vast tent. The stars are the holes in the tent where the light of heaven penetrates to earth. Each poet views a particular star but the light pouring through is identical. These poets form a "tradition," therefore, but not in the usual sense of a body of customs and knowledge that is passed down through the generations. The tradition is eternally present.

If we talk of tradition today, we no longer mean what the eighteenth century meant, a way of working handed down from one generation to the next; we mean a consciousness of the whole of the past in the present. Originality no longer means a slight personal modification of one’s immediate predecessors... it means the capacity to find in any other work of any date or locality clues for the treatment of one’s own personal subject matter.

This is from yet another poet, W.H. Auden, writing in 1941. Certainly, Finnegans Wake and The Cantos both contain "a consciousness of the whole of the past in the present." Epiphanies, luminous details, minute particulars, barbs of light each interpenetrate one another like gems in a net or blossoms on a dark bough. Past, present and future are merely turnings of the dazzling "collideorscape." All exists at once in chaotic coherence.

Cosmos-making

There is a network of these moments, a network that a handful of sensitive souls occasionally become aware of. Sacred spots are cordoned off. Points of hierophany are recognized (cults may later be built around these and the light occluded, but that's another story) and these points echo off similar points within both history and geography. In modern secular societies such points are becoming difficult to locate, but in ancient times they were clearly delineated and revered.

Whenever the dullness of the profane was left behind, whenever life grew more intense in whatever way, through honor or death, victory or sacrifice, marriage or prayer, initiation or possession, purification or mourning, anything and everything that stirred a person and demanded a meaning, the Greeks would celebrate with fluttering strips of wool, white or red for the most part, which they tied around heads, or arms, or to a branch, the prow of a ship, a stature, an ax, a cooking pot.

This is from Robert Calasso's masterwork, The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony. In Ancient Greece these colourful woolen strips could often be found. People realized the porosity of the tent. The meaning of these strips was meaning.

What was it those woolen strips, those tassels represented? An excess, a flowing wake that attached itself to a being or thing. And at the same time a tether that bound that being or thing.

Meaning itself binds. To live without significance is to live without responsibility. In modern existence all features are levelled, made smooth. No moment is greater or lesser than any other. There is no excess and there is no scarcity. All is explained. Sudden metamorphosis is impossible. No one is subjected to the arbitrary whims and fancies of the gods. We are rational and free. This could be anywhere. This could be everywhere. But this was not always so. What was gained and what was lost?

It was a momentary surfacing of a link in that invisible net which enfolds the world, which descends from heaven to earth, binding the two together and swaying in the breeze. Men wouldn't be able to bear seeing that net in its entirety all the time...

All these woolen strips, these vain, winged tassels, were the nerves of the nexus rerum, the connection of everything with everything else, which alone gives meaning to life.

Meaning may have been lost. But only temporarily. The old web of hierophanic ruptures is intact. Nodes are even now occasionally added to it, instants of "busting thru," that are remembered by the network even if they are hastily dismissed from the minds of their modern experiencers. But in many places around the world these points are still marked and recalled.

In Japan, sacred areas or trees or rocks are enclosed and sanctified with shimenawa ropes. Small Jizo statues are found along quiet forest trails. A single mountain in Shizuoka has 88 stations which mirror in miniature the grand pilgrimage of the 88 temples of the southern island of Shikoku. All these represent still visible "nerves of the nexus rerum," that are really much older than Shintoism or Buddhism. They are the eastern-most nodes of an unbroken web of significance that also contains the "winged tassels" of Ancient Greece.

Flickering Flakes

And of course this web is also marked by synchronicities -- meaningful coincidences. That things coincide is really not all that special. Right now my fingers are coinciding with this keyboard. Synchronicity, though, only exists because of the meaning that particular individuals assign it. Like a luminous detail, like a hierophany, a synchronicity is singular and subjective. What one person views as being highly profound another will call sheer nonsense. The outline of the "Divine Jesus" constantly shifts and shimmies. It's hard to get a bead on it.

That's why not everything syncs. Nor is everything sacred. How could it be? A world where everything is sacred is a world where everything is profane. Meaning is marked by differences -- luminous differences. P.K. Dick could find revelation in trash and sync savants can hear alchemy in pop, but the stars really shine in the imaginations of these poets.

Art is primarily where the woolen strips are now tied. And it is the artist who apprehends that the strips have already been tied. The object, whatever it is, only becomes art at that moment. The artist attempts to capture this vision -- in words and music and picture and form -- and if he or she successfully does this the moment is recreated. The fading coal flares anew.

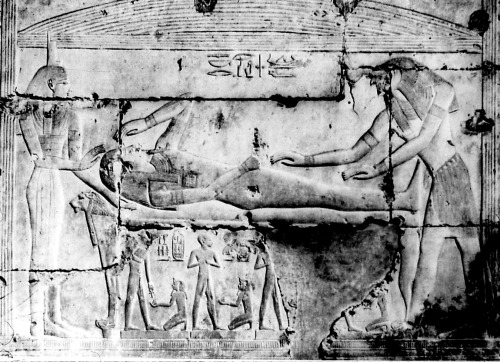

Already this has gone on too long. Already I've failed in this "method." Ezra Pound also called the assembling of luminous details the gathering of "the limbs of Osiris." Osiris is equivalent to Blake's Divine Jesus or Joyce's Finn. Maybe I'll be lucky enough stumble across a bit of dandruff.

i.e. it coheres all right

even if my notes do not cohere.