"Here's to Waste !" Tarr announced loudly to the two waiters in front of the table. "Waste, waste; fling out into the streets: accept fools, compromise yourselves with the poor in spirit, it will all come in handy! Live like the lions in the forests with fleas on your back. Above all, down with the Efficient Chimpanzee ! "

-- Tarr (1928), Wyndham Lewis

1922, year one of the

Pound Era, was also the year that James Joyce, with the immense aid of his editor Ezra Pound, published

Ulysses. The themes and literary/historical allusions of

Ulysses and

The Waste Land

are so interwoven, so mutually reflecting, that many commentators

accuse Eliot of outright plagiarism. Joyce himself in a letter wrote a

short parody of Eliot's poem.

But we shall have great times,

When we return to Clinic, that waste land

O Esculapios!

(Shan't we? Shan't we? Shan't we?)

And while Joyce played

with this -- Eliot is one facet of the compound character of

Shawn the Forger in the Wake -- he never made any formal accusations

against the poet. A more interesting thesis is that Joyce, Pound, Eliot,

and likely Yeats and

others were in full cahoots, all consciously involved in advancing a certain agenda. In Jessie Weston's terms, they were

forces and

agents of

evolution.

Dublin, on June 16th, 1904, is also portrayed in

Ulysses as being a

waste land.

It is not until the the thunder claps, halfway through the book, that

the long anxious wait for the summer rain is interrupted. This thunder is also heard in part five of

The Waste Land, "What the thunder said." A single violent blast is heard three times: "

DA."

In his notes, Eliot explains that this anecdote is taken from part 6 of the

Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad.

The story goes that (in Eliot's order) men, the Devas (gods), and the

Asuras (demons) each interpreted the terrible syllable of the primal

thunder as the wisdom they respectively most needed to hear.

"Datta, dayadhvam, damyata" (Give, sympathise, control).

In

Ulysses,

the coming of the Thunder and rain is followed by an

incredible babble of voices, of styles of writing, and then by the

complete breakdown of the conventional experience of space and time.

This culminates, as I have

written, in Stephen's shattering of the brothel's chandelier with his staff and the rupture into eternity -- "

ruin of all space, shattered glass and toppling masonry." Pound describes the instant of rupture in a letter to his father:

The 'magic moment' or moment of metamorphosis, bust thru from quotidien into 'divine or permanent world.' Gods, etc.

The

voice of the thunder, then, conjures several things at once. It bestows a

new, almost angelic or magical, language upon mortals, and simultaneously causes an incredible confusion of tongues, a complete breakdown in

existing communication.

It is the combination, the

overlay, of the Day of Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit first descended

and granted the apostles the gift of tongues, and the fall of the Tower

of Babel, the fourth fall after Lucifer, Adam and the

Flood. Babel and Pentecost represent, respectively, the Fall and

Redemption of language. The voice of the thunder reminds us that both

are really simultaneous events. A gate or door that opens both ways.

Lukkedoerendunandurraskewdylooshoofermoyportertoo-

ryzooysphalnabortansporthaokansakroidverjkapakkapuk.

It

is within this electrically-charged clap of thunder, in

the very thick of both confusion and grace, that we find ourselves. It is just before dawn of the

third day, in the infinite space between collapse and renewal, between

oblivion and utopia. It is as if we are hearing

the command from the sky for the first time. Giambatista Vico, a major

source for Joyce, arrives at the same story as the

Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad,

intuitively and in ignorance of the much older Indian scripture:

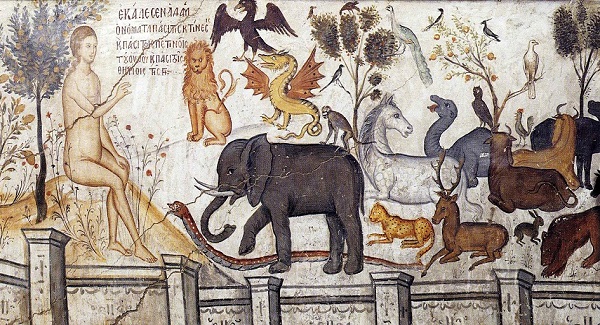

Thereupon

a few giants, who must have been the most robust, and who were

dispersed through the forests on the mountain heights where the

strongest beasts have their dens, were frightened and astonished by the

great effect whose cause they did not know, and raised their eyes and

became aware of the sky. [....T]hey pictured the sky to themselves as a

great animated body, which in that aspect they called Jove, the first

god of the so-called greater gentes, who meant to tell them something by

the hiss of his bolts and the clap of his thunder. And thus they began

the natural curiosity which is the daughter of ignorance and the mother

of knowledge, and which, opening the mind of man, gives birth to wonder. --The New Science (1725)

Becoming

first aware of the sky, in wonder, we learned generosity, compassion

and self-control. These are lessons which we are being compelled to

learn again. And, should we choose to listen, the voices can be heard

from both the Overworld and the Underworld, from the gods or from the seers.

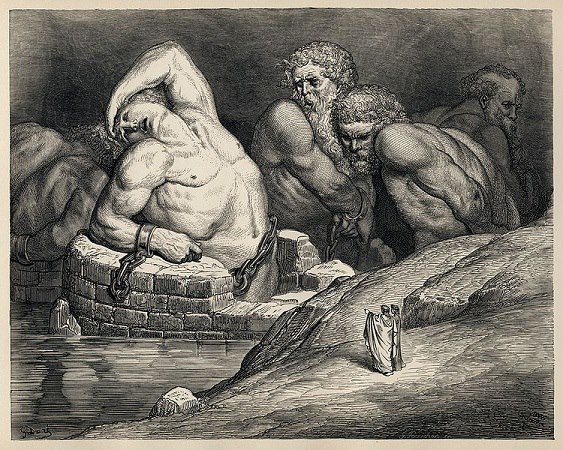

Ulysses

Ulysses, being a literary metempsychosis of

The Odyssey,

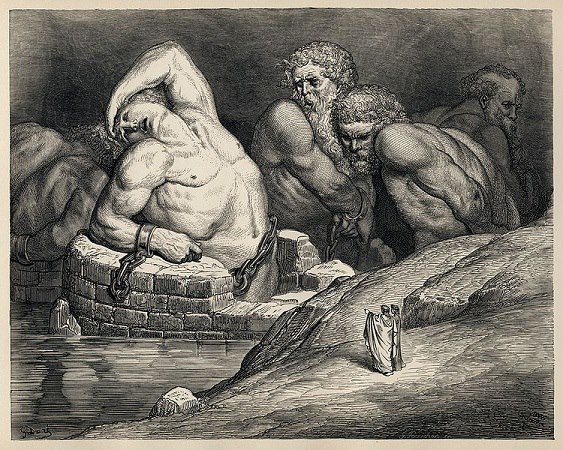

also depicts a descent into Hades. Odysseus, as in the first Canto,

descends to consult the seer,

Tiresias. There is no obvious counterpart

to Tiresias in

Ulysses, but looking deeper we find that the threshold aspect of the blind prophet is shared by the mysterious "

chap in the macintosh" in the "Hades" episode. This is a man who is unknown, both there and not there. According to critics like

Nabakov, this man is none other than Joyce himself. So, to complete the equation, Joyce

is Tiresias.

Tiresias (and I intend to write much more on this all-important figure) is central to the

Waste Land. Admittedly central. Here is Eliot in his notes:

Tiresias, although a mere spectator and not indeed a

'character', is yet the most important personage in the poem, uniting all the

rest. Just as the one-eyed merchant, seller of currants, melts into the

Phoenician Sailor, and the latter is not wholly distinct from Ferdinand Prince

of Naples, so all the women are one woman, and the two sexes meet in Tiresias.

What Tiresias sees, in fact, is the substance of the poem.

Tiresias,

who had the unique opportunity of being both a man and a woman, was

blinded by Hera for revealing to her divine husband, Zeus, that women

enjoy far greater pleasure in lovemaking than men. Zeus in his

compassion for Tiresias could not undo the spell of his wife, but he did

grant him the gift of prophecy, of sight without sight.

The Duir Is Ajar

Many, including Robert Anton Wilson and even Joyce himself, have concluded that the nearly sightless author of

Finnegans Wake also possessed

prophetic vision. Was Joyce, as long as we are engaged in unhinged speculation, also blinded for revealing secrets of the

hieros gamos, of hierogamy, to the uninitiated? And could this be another reason why Pound advised caution in his editing of Eliot's

Waste Land?

There are several ways to approach the Wake as a prophetic text. One technique, which Joyce directly refers to in the Wake (insofar as he directly refers to anything!) is sortilege. This essentially consists of flipping through a major work, such as the Bible or Virgil's epic, and letting one's finger "randomly" fall upon a salient passage. This works very well with the Wake.

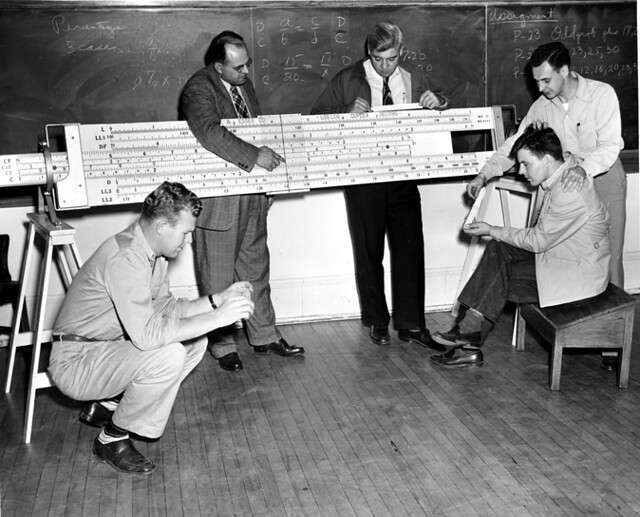

Another method to consult Joyce's oracle of the dark, however, is not as obvious, yet it has to do with the deliberate structure of his architectonic word cathedrals. The number of pages and the number of lines on each page of Joyce's books, it seems, were carefully considered and crafted. While

Ulysses had several subsequent editions of varying page lengths, Joyce makes it clear that the original 732-page first edition was the most vital rendering. He refers to this first edition in the Wake:

...the cut and dry aks and wise

form of the semifinal; and, eighteenthly or twentyfourthly, but

at least, thank Maurice, lastly when all is zed and done, the pene-

lopean patience of its last paraphe, a colophon of no fewer than

seven hundred and thirtytwo strokes tailed by a leaping lasso...

If the page numbers are significant then dates can be determined from them. The first time I saw this type of correlation is of

page 111 of the Wake with Robert Anton Wilson's death on January 11th.

...peraw raw raw reeraw puteters out of Now Sealand in spignt of the

patchpurple of the massacre, a dual a duel to die to day, goddam and

biggod, sticks and stanks, of most of the Jacobiters...

And if we can consult the Wake like this, as an oracle whose pages may correspond to specific dates, then what happens when we plug in, so to speak, extremely crucial dates like 9/11, one of the events that Green focuses on in his video?

There is no page 911 in the Wake -- it "ends" on page 628 -- but in Europe where Joyce was writing the Wake, 9/11 is written as 11/9. Accordingly, if anything is to be found it will be found on page 119.

Examining this page, there is nothing written there, seemingly, which could remotely be said to refer to 9/11. There

is something, though, that stands out. Two

sigla, part of Joyce's "

scribbledehobble," are included on the page. A

delta symbol is directly underneath an

E with its three prongs pointing to the bottom of the page. The overturned E is HCE, the Mountain, just as the delta is ALP, the River.

If we view this pictogram with prophetic eyes, however -- with the perhaps crazed intention to allow the gods and ancestors to speak to us anew about our own time -- it is easy to squint and see a jet airplane flying towards a twin pair of towers in close proximity. The symbolism is really not that far from Joyce's.

A Delta Airlines

flight, while not directly involved in the attacks, was also suspected of being hijacked and was ordered to land. The Towers, like the Mountain, are immobile and like HCE were brought crashing down by a fluid, feminine force traversing riverine courses in the sky.

There is one more notable element to this pictogram. Whether any of this was intentional or not, and it would stretch the bounds of the possible if it was, the delta and the E are not immediately adjacent on the page. They are separated by a lowercase

d.

This d, in the present froth-mouthed analysis, is no randomly placed letter. It is the key to the whole glyph. D in the Old Irish alphabet, whose eighteen letters correspond to the eighteen chapters of

Ulysses, is

Duir, the Door. This is also the "

DA" of the thunder, the portal -- "

Lukkedoerendunandurra..." -- by which the will of the gods reach this Earth.

I've compared this previously to

Da'at on the Tree of Life, the very barred gates of Paradise. Metaphorically, if in no other sense, and as Jake Kotze and others have long suggested, the jet that first hit the tower on 9/11 passed through a portal, a

stargate, after which time and space were momentarily overthrown.

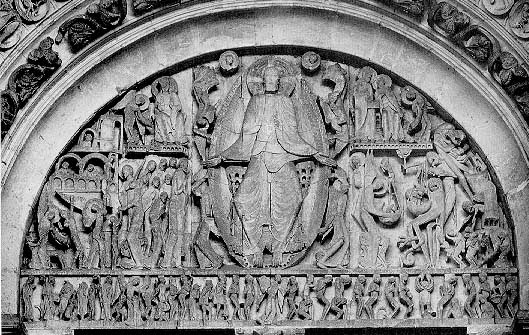

The wider context

of this page surprisingly supports this interpretation. Page 119 is hugely significant for the entire Wake. The whole mystery may be unlocked here. In fact, this page is where the

Tunc page of

The Book of Kells is introduced, with the inference that it is a pictorial synecdoche of the entire Wake. In his

Skeleton Key To Finnegans Wake, Joseph Campbell writes:

The reader of Finnegans Wake will not fail to recognize in this page

something like a mute indication that here is the key to the entire

puzzle: and he will be the more concerned to search its meaning when he

reads Joyce's boast on page 298: "I've read your tunc's dismissage."

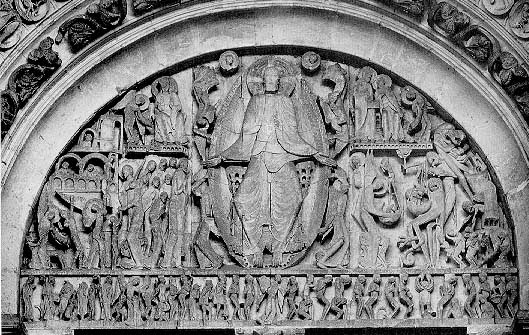

The Tunc page depicts Christ on the Cross between the two, likewise crucified, thieves. One thief ridicules Christ and the other asks for Christ to remember him, and for this request is promised Paradise. The entire cycle, also revealed in the serpentine, ouroboric border of the Tunc page, is present. One thief descends and one thief ascends as the veil is rent, the thunder claps and the towers fall. It is accomplished.

What is the city over the mountains

Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air

Falling towers

Jerusalem Athens Alexandria

Vienna London

Unreal -- The Waste Land

It would be crass to call any of this "predictive programming." Nothing clear is being programmed, and it is highly unlikely that Joyce or Eliot or

The Book of Kells predicted 9/11. Nonetheless, it is there. Instead, contemplation of the prophetic shifts perception to sight beyond sight. Traumatic and singular events, planned or not, cause us to "

bust thru." The door suddenly opens.

This sequence loops like a vinyl record skip -- the statically charged instant between the clap of thunder and the coming of the rain, the last days of the Waste Land. And, by taking on the outwardly blind eyes of the prophet, the signs are everywhere evident.

All Go Into The Dark

Alan Green's "

Suicide Kings" was, on this occasion, the augur leading back into the desert. After reading Weston's

From Ritual to Romance, I decided to reread Conrad's

Heart of Darkness and T.S. Eliot's

The Waste Land. Living in Japan, I do a lot of my reading on the train. One day, just as I was about to finish

Heart of Darkness and begin reading Eliot, I decided on a whim, as I had the afternoon off, to watch Christopher Nolan's

Interstellar. I got through the Conrad on the train and was just wrapping up

The Waste Land in the theatre as the movie started.

I was truly not expecting much from this film at all, and I was actually only there because I wanted to see

Interstellar before listening to the (very sadly defunct)

Moon Room Cinema podcast on it by Mark LeClair and Alex Fulton. Not long into it, though, I realized that Nolan's largely mediocre film was exploring precisely the same themes as were haunting myself.

The central "character" of this film is a black hole. At one point it is described as "

the literal heart of darkness." This got me sitting straight up in my seat. Even more cortex-crackling was the fact that, in a key scene, a "ghost" knocks a book by T.S. Eliot among others off a bookshelf. In my slobbering astonishment came the instant recollection that I had just finished reading Eliot's poetry.

Later, not believing my senses, I checked online to see if this actually occurred in the movie. A review from the

Telegraph informed me that it was even more uncanny, more improbable, than I had imagined:

Coop has faith that his daughter Murph (played by Mackenzie Foy,

and later, as an adult, by Jessica Chastain) is one of them. She’s

troubled at night by strange shufflings from her bookcase – a ghost, she

believes, and one with a flair for foreshadowing, given the way it

pointedly knocks volumes by Joseph Conrad and T.S. Eliot off the shelf.

I had literally, without previously knowing anything about

Interstellar, just completed reading works by

both Conrad and Eliot immediately before watching the flicking film! How is this possible? What dream realm had I entered into? Had the "ghost" also decided to contact me?

Further digging on the web confirmed that

Nolan was very consciously playing with these themes. In an interview he stated:

I imagined Doctor Mann a bit like from Joseph

Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness.” You have Kurtz, this character that you

hear about. Everybody says, “Oh, he’s great. Maybe you’ll get to meet

him.” I really love the idea for an audience to go, when they see him,

“Oh, it’s Matt Damon. It’s going to be okay.”

Dr. Mann, a brilliant yet twisted scientist/explorer stationed on an uninhabited planet orbiting the black hole, was also Kurtz. All of the pieces snapped into place.

I in no way want to defend

Interstellar as a great work of art, or even less so to affirm its very questionable message. The conclusions of this film, when its surface is scratched, are quite disturbing. That it actively promotes a transhumanist agenda seems obvious, and there is no better exploration of this angle than in the LeClair and Fulton podcast I mentioned above. But, given the deep weirdness I was awashed in, this is by no means the entire story.

Nolan

knows. It's hard to avoid this conclusion. The "ghost" of the bookshelf turns out to be Murph's father attempting to communicate to her via gravity waves from the heart of the black hole in a Borgesian labyrinth of the imagination apparently constructed by humanity's four-dimensional descendents. A few startling claims are implied here about the nature of the "conspiracy" which rules our present world.

It is "benign," or at least it is utilitarian -- it is willing to make huge sacrifices for the the greater good. The beings involved are explicitly "

agents" of our "

evolution." They also "exist" outside or beyond our usual conceptions of time. The entire past and future exists as an extended present for these hyper-advanced beings. They attempt to communicate to us, to orchestrate events for us, through synchronicity, through paranormal phenomena, through signs and wonders, through the pops and scratches of the programmed recording.

They dwell, in other words, in the prophetic space I've been trying to articulate throughout this essay. All mere human representatives of this shadowy hierarchy do no more than dissolve into the all powerful void.

O dark dark dark. They all go into the dark,

The vacant interstellar spaces, the vacant into the vacant,

The captains, merchant bankers, eminent men of letters,

The generous patrons of art, the statesmen and the rulers,

Distinguished civil servants, chairmen of many committees,

Industrial lords and petty contractors, all go into the dark,

-- "East Coker"

In the heart of darkness, at the core of the singularity, time is maximally condensed. All times and places are simultaneously present and not present. As we travel away from the dark centre, time slows, things begin to solidify. Nolan depicts various "levels" of time dilation within the film. Scant moments close to the black hole are equivalent to the passing of decades on Earth.

This portrayal of a multi-layered yet simultaneous continuum of time has an obvious resonance with another of Nolan's films:

Inception.

Inception is

Interstellar turned inside out. As Spock sang, "Outer Space/Inner Mind." The profound implication is that the black hole, the ultimate singularity where all physical laws are overturned, is the exact same "place" as the deepest depth of our own unconscious.

And, as this is a point beyond and through all dichotomies, it is neither individual nor collective (as Jung taught), neither good nor evil. This "fourth-dimensional" conspiracy is

identical to the wellhead of human/divine imagination. The transhuman, implying a hyper-technological control grid, is revealed to be no more advanced than the technologies of myth and language. It is the Word that emerges first, and perpetually, from the the void.

If the lost word is lost, if the spent word is spent

If the unheard, unspoken

Word is unspoken, unheard;

Still is the unspoken word, the Word unheard,

The Word without a word, the Word within

The world and for the world;

And the light shone in darkness and

Against the Word the unstilled world still whirled

About the centre of the silent Word. -- Ash Wednesday

Contemporaniety

The poet or artist, equipped with nothing more hi-tech or magical than a pen or a brush is the ultimate conspirator. If the poet senses the injustice of the dominant spell, he or she incants words and casts a new enchantment. This, as Robert Duncan asserts, is precisely the function of poetry.

The

power of the poet is to translate experience from daily time where the

world and ourselves pass away as we go into the future, from the

journalistic record, into a melodic coherence in which words -- sounds,

meanings, images, voices -- do not pass away or exist by themselves but

are kept by rhyme to exist everywhere in the consciousness of the poem.

The art of the poem, like the mechanism of the dream or the intent of the tribal myth and dromena,

is a cathexis: to keep present and immediate a variety of times and

places, persons and events. In the melody we make, the possibility of

eternal life is hidden, and experience we thought lost returns to us.

The poet, insofar as he or she wishes to share this possibility of eternal life, cannot be considered, however his or her poetry is used and abused by the dominant illusion, as evil. This, though, becomes a Gordian Knot to disentangle. The conspirators, whoever or whatever they are ultimately, also operate from this timeless present. The rituals they enact, however, are intended to conceal rather than to reveal, to hide the truth of eternity in an endless Waste Land.

And yet, are they betrayed by their own machinations? Or are they, on a deeper level -- closer to the black hole, even more coterminous with the clap of the thunder -- acting at cross purposes to their own conscious intentions?

The singularity is its own poetry. As in the earliest Hindu verse, in fact the oldest known literature, it is unclear who came first, the Gods or the

Rishis? Behind the Archons, dark poets themselves, are the blind seers, the visionaries, the makers. And what they see is the pointless point, the

hieros gamos of Being and Nothingness.

If, as Pound began to see in The Spirit of Romance, "all ages are contemporaneous," our time

has always been, and the statement that the great drama of our time is

the coming of all men into one fate is the statement of a crisis we may

see as ever-present in Man wherever and whenever a man has awakened to

the desire for wholeness in being.

The crisis --

our crisis -- has always been present. There was never a time where the Waste Land did not entrap us all in its desolation. Sterility, winter and death are all pervasive. And yet so is everything else. Yet another genocide. Yet another flower blooms. Only the illusion has a sequence. Anything real does not recognize the bounds of cause and effect. Great literature, free and open art, can only reflect this.

These poems where many persons from many times and many places begin to appear -- as in The Cantos, The Waste Land, Finnegans Wake, The War Trilogy [H.D.], and Paterson [William

Carlos Williams] -- are poems of a world-mind in process. The seemingly

triumphant reality of the War and State disorient the poet, who is

partisan to a free and world-wide possibility, so that his creative task

becomes the more imperative. The challenge increases the insistence of

the imagination to renew the reality of it own. It is not insignificant

that these "poems containing history" are all products of a movement in

literature that was identified in the beginning as "free" verse.

The Rosebud, The Rosebud

Inevitably, I was also compelled by my journey up the river to rewatch

Apocalypse Now. Colonel Kurtz, in the throes of fever and final disintegration, reads aloud the poetry of T.S. Eliot:

I should have been a pair of ragged claws

Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.

This is another image of the Waste Land; ragged claws, cancer. After this I watched for the first time,

Hearts of Darkness -- the excellent documentary on the making of

Apocalypse Now.

It appears that by invoking the Chapel Perilous, the journey up the river, the harrowing of hell, one invites dissolution. Go figure. Martin Sheen has a heart attack and nearly dies, the film's production teeters on the edge of collapse, and Coppola himself suffers a near total breakdown, envisioning himself as the doomed Kurtz. The ragged claws uncover the blackest nightmares.

And from this documentary I learned that Coppola's was not the first attempt to translate Conrad's vision into film. It first was tried by none other than Orson Welles. Welles was eventually thwarted by budgetary restraints and the outbreak of World War Two, but

Heart of Darkness continued to dominate his imagination.

Many critics have suggested, in fact, that the next film he would produce and direct,

Citizen Kane -- considered by some to be the best film ever made -- is largely a reworking of

Heart of Darkness. Kurtz, no longer a company trader in a remote outpost in the Congo, becomes Kane, one of the richest and most powerful men in the U.S.A., the postwar centre of world empire.

This is far closer to the opening pages of

Heart of Darkness. The real Fall, the real slide into darkness, is not into wilderness but to the apparent heights of civilization. It is Babylon, not Eden, which is the true site of our downfall.

The River in

Citizen Kane is not as obvious, but it is actually partly alluded to in the initial newsreel announcing Kane's death:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

Kane is Khan and his pleasure dome, Xanadu, containing all the beautiful art objects of history, brings no real pleasure to himself or anyone else. He is alone. He is forsaken like the Sibyl of Cumae. The River Alph is, of course, ALP the ever-flowing, delightful yet indifferent. HCE is Kane is Khan is Kurtz is Coppola is Welles and even Nolan, creators who fail to properly revere the River.

And for both Kurtz and Kane the epiphany of their utter foolishness arrives at the bitter end. They are united by their last words: Kurtz's "

Horror" becomes Kane's "

Rosebud." These words represent different angles on an identical scene, opposite sides of the portal to Paradise. The Horror is without and Rosebud is within. Kane beholds his lost innocence, represented by carefree winter sledding and the warmth of his mother's love, while Kurtz looks to the utter devastation just beyond the threshold.

Both, though, show the way back. Rosebud also implies the Rose of Dante's

Paradiso, a vision of lost eternity but an eternity still in bloom. This is a vision that for Dante is only beheld after emerging Christ-like from three days in darkest Hell. Once more this powerful imagery surfaces. That Conrad was also alluding to this is shown just before Kurtz's revelation of "the Horror."

Anything

approaching the change that came over his features I have never seen

before, and hope never to see again. Oh, I wasn't touched. I was

fascinated. It was as though a veil had been rent. I saw on that ivory

face the expression of somber pride, of ruthless power, of craven

terror—of an intense and hopeless despair.

And They Blink

"

As though a veil had been rent." Kurtz's face in private apocalypse is being compared to the supernatural ripping of the veil of the Temple of Solomon at the precise moment of Christ's death, accompanied by thunder and earthquake. For this brief instant the blazing light of the Holy of Holies, the light of lost Paradise, shone blindingly on all the world. Flashes of this occasionally shine anew. Kurtz experiences it as total horror.

And, behold, the veil of the temple was rent in twain from the top to the bottom; and the earth did quake, and the rocks rent;

Marlow, the sole witness to Kurtz's terrible passing, is tasked with returning to London and meeting with Kurtz's bereaved fiancée. Marlow is haunted by Kurtz's last words. He can hear them emanating in hoarse whispers from somewhere just behind of or from within the disgustingly quotidian street scenes of the Empire's Necropolis.

I found myself back in the sepulchral city resenting the sight of people hurrying through the streets to filch a little money from each other, to devour their infamous cookery, to gulp their unwholesome beer, to dream their insignificant and silly dreams. They trespassed upon my thoughts. They were intruders whose knowledge of life was to me an irritating pretence because I felt so sure they could not possibly know the things I knew.

Still in Saigon. Marlow, initiated by the death of Kurtz, is alone awake within the Waste Land. Eliot, also aware of this cursed transcendence, returns to it directly in his epigraph to the

The Hollow Men (1925). No longer advised against it by the editing pencil of Ezra Pound, he points to the immediate aftermath of Kurtz's death:

Mistah Kurtz -- he dead

Back to the whimpering hollow men, the stuffed men. We are, in his poetic progression, still in the Waste Land. And yet Kurtz is now dead, and the world ends without a bang. This condition is still being explored in his final and monumental epic,

Four Quartets (1945), yet ultimate release is yet to come. Like Kurtz's Marlow, his critique of the oblivious denizens of the sepulchral city is brutal:

Neither plenitude nor vacancy. Only a flicker

Over the strained time-ridden faces

Distracted from distraction by distraction

Filled with fancies and empty of meaning

Tumid apathy with no concentration

Men and bits of paper, whirled by the cold wind

That blows before and after time,

Wind in and out of unwholesome lungs

Time before and time after.

Time is not conquered here, in the modern Waste Land which even now persists, dazzling by technology and the ecstasy of meaningless communication.

Not here

Not here the darkness, in this twittering world.

I can't help but be reminded here of Nietzsche's words from

Thus Spake Zarathustra (1883), which surely must have pierced the mind of Eliot as well:

"Alas, the time is coming when man will no longer give birth to a

star. Alas, the time of the most despicable man is coming, he that is no

longer able to despise himself. Behold, I show you the last man.

"'What is love? What is creation? What is longing? What is a star?' thus asks the last man, and he blinks.

"The

earth has become small, and on it hops the last man, who makes

everything small. His race is as ineradicable as the flea-beetle; the

last man lives longest.

"'We have invented happiness,' say the last

men, and they blink. They have left the regions where it was hard to

live, for one needs warmth. One still loves one's neighbor and rubs

against him, for one needs warmth.

"Becoming sick and harboring

suspicion are sinful to them: one proceeds carefully. A fool, whoever

still stumbles over stones or human beings! A little poison now and

then: that makes for agreeable dreams. And much poison in the end, for

an agreeable death.

"One still works, for work is a form of

entertainment. But one is careful lest the entertainment be too

harrowing. One no longer becomes poor or rich: both require too much

exertion. Who still wants to rule? Who obey? Both require too much

exertion.

"No shepherd and one herd! Everybody wants the same,

everybody is the same: whoever feels different goes voluntarily into a

madhouse.

"'Formerly, all the world was mad,' say the most refined, and they blink..."

A horrible prophecy fulfilled! The inability, and even an ironic and self-conscious disinterest, to give birth to a star, to possess chaos within. Men and bits of paper whirling about. Take a selfie as you commit yourself to the asylum. Blinders to the horror. Rosebud completely forgotten. Distracted by distraction. And is that it? The last man, the stuffed man, in ceaseless perpetuity? This is Pound's reign of

usura, of universal sterility and sanitation, bringing whores to Eleusis, conducting rituals and spectacles to perpetuate the Waste Land.

Pound often recalls that Dante had those guilty of usury and sodomy suffering in the same circle of the Inferno. Both, according to Pound's reading, have committed offenses against the fecundity of Nature, both have contributed in the attempt to block Her energies, to transform bounty into scarcity and waste.

To be generous to both poets, we can interpret "sodomy" not as any particular proclivity or orientation -- a dancing star need not be a child, the union of opposites need not come from those of different genders -- but as a symbol of the waste of productive or creative potential. The name of this sorcery is

usura, its means are sodomy. We are all getting shafted.

As Marlow reluctantly meets Kurtz's fiancée, the inevitable question surfaces: what were his last words? Marlow is on the razor's edge of revealing the whole terrible mystery, but he can't.

I was on the point of crying at her, 'Don't you hear them?' The dusk

was repeating them in a persistent whisper all around us, in a whisper

that seemed to swell menacingly like the first whisper of a rising wind.

'The horror! The horror!'

He ends up lying: Kurtz's last word was her name. In tragicomic contentment, she remains asleep. Marlow has committed the unforgivable sin. He has bore false witness to vision. He has blasphemed against the Holy Spirit. He has used love to perpetuate a falsehood and, like Perceval at the Grail Castle, his failure to state the truth perpetuates the binding illusion.

It seemed to me that the house would collapse before I could escape, that the heavens would fall upon my head. But nothing happened. The heavens do not fall for such a trifle. Would they have fallen, I wonder, if I had rendered Kurtz that justice which was his due? Hadn’t he said he wanted only justice? But I couldn’t. I could not tell her. It would have been too dark—too dark altogether....

And in this the terrible secret of our enchantment, of the Waste Land, is revealed. Even with the traumatic events of recent history that Green explores, the heavens did not fall. We continue to blink. They are designed to perpetuate the lie, to bind us in fear yet also in "love." Usury and "sodomy." Real justice comes only in full, open-eyed acceptance of the darkness. The veil has been rent and we are in hell, but only by awakening to this do we arrive at the dawn of the third day.

Dancing Lizards

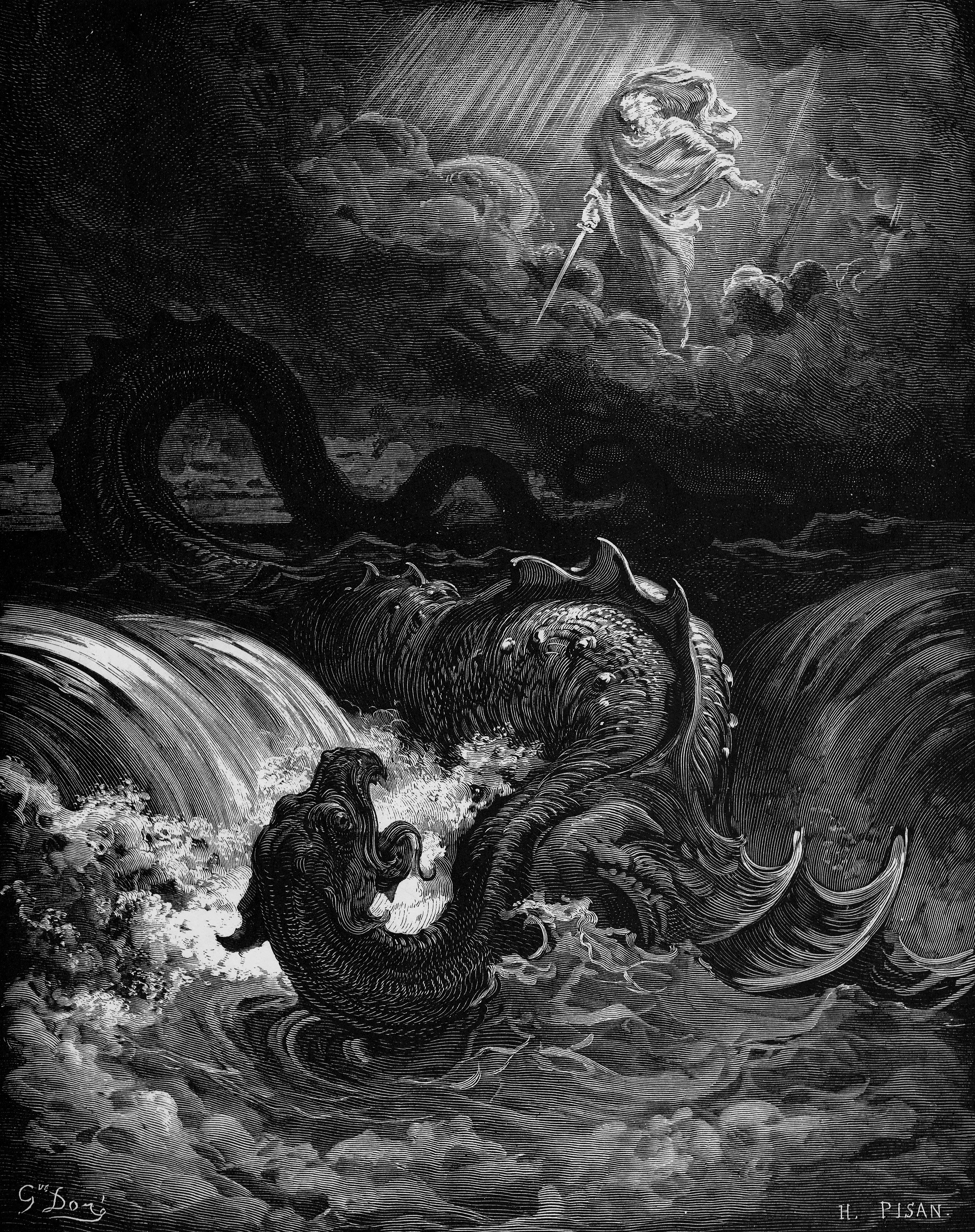

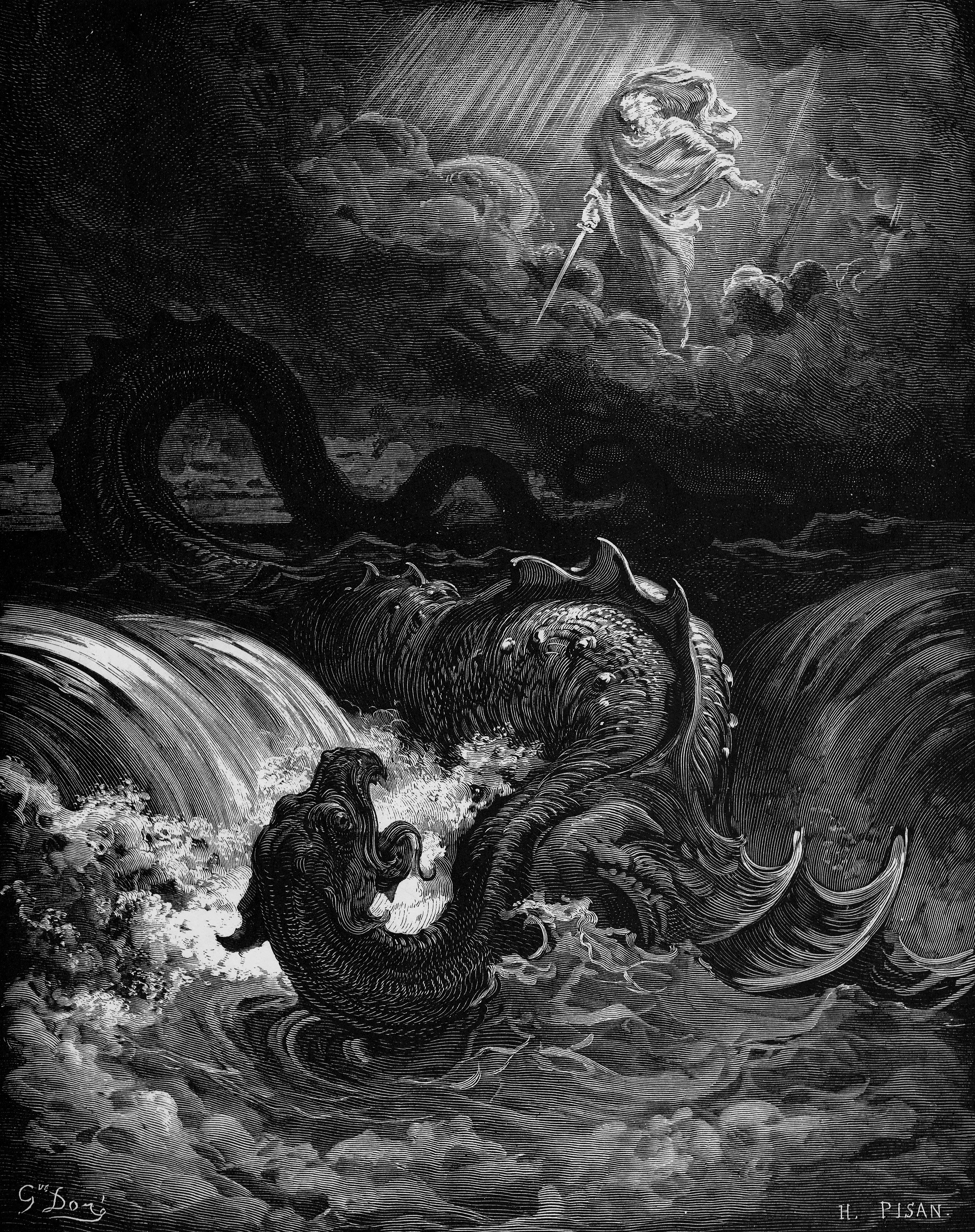

And at this moment many things happen at once, all of the stories converge. The castle becomes disenchanted, the beast is slain. Northrop Frye explores this:

Another monster slain by Jesus in his Easter victory over death and hell: the leviathan of the old Testament, a sea-monster who is the sea, as he is death and hell, and also the devil, the serpent of Paradise, described in [Eliot's] The Rock as "the

great snake at the bottom of the pit of the world." In the the Bible he

or a similar monster is also identified with the kingdoms of tyranny,

Egypt, Babylon, and the Phoenician city of Tyre. Thus the world that

needs redemption is to be conceived as imprisoned in the monster's

belly, whence the Messiah, following Jonah, descends to deliver it.

The triumph over death and hell is also the conquest of Leviathan. This is our old enemy -- the

State and Church, space and time, the confining monster's belly of our own perception. This is what has been transcended. The

hieros gamos of subject and object. Frye, in

Anatomy of Criticism, points to another three-day battle against the beast in Edmund Spenser's

Faerie Queene (1590):

In

Spenser's account of the quest of St. George, the patron saint of

England, the protagonist represents the Christian Church in England, and

hence his quest is an imitation of that of Christ. Spenser's Redcross

Knight is led by the lady Una (who is veiled in black) to the kingdom of

her parents, which is being laid waste by a dragon. The dragon is of

somewhat unusual size, at least allegorically. We are told that Una's

parents held "all the world" in their control until the dragon

"Forwasted all their land, and them expelled." Una's parents are Adam

and Eve; their kingdom is Eden or the unfallen world, and the dragon,

who is the entire fallen world, is identified with the leviathan, the

serpent of Eden, Satan, and the beast of Revelation. Thus St. George's

mission, a repetition of that of Christ, is by killing the dragon to

raise Eden in the wilderness and restore England to the status of Eden.

Similar examples can be presented almost without end. As Frazer and Weston taught, this is at the heart of all myth. In its simplest parallel this is the turning of day into night, of summer into winter. From the work of Weston and Pound and Joyce and Eliot, however, comes word of another cycle, both larger and more intimate. There arises the sense that the winter of our collective psyche is unseasonably long and cold. And, more alarmingly, that there is nothing "natural" about this. The "King" continues to be killed, but the Waste Land only expands.

And yet that is the biggest lie of all. The cycle has not become stuck. There is a point beyond it, a point encompassing the total cycle of cycles. Poetry, as Duncan affirms, is

the counter-magic. Eliot, in

Four Quartets, finally and beautifully shows us the way out of the Waste Land:

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement.

And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered. Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.

The still yet dancing point

is the Resurrection, but I think we miss out by confining this vision to the relatively narrow bounds of orthodox Christianity, even though Eliot identified with this himself. As in the Naasene teachings, the Mystery of the Christ is really the culmination of

all the Mysteries -- the divine marriage of Matter and Spirit within history -- and Eliot is keenly aware of this. He goes on to match this "

still point" with Krishna's revelation of the

vishvarupa, his "universal form" containing all gods and demons, to Arjuna on the eve of battle.

Out of countless eyes beholding,

Out of countless mouths commanding,

Countless mystic forms enfolding

In one Form: supremely standing

Countless radiant glories wearing,

Countless heavenly weapons bearing,

Crowned with garlands of star-clusters,

Robed in garb of woven lustres,

Breathing from His perfect Presence

Breaths of every subtle essence

Of all heavenly odours; shedding

Blinding brilliance; overspreading-

Boundless, beautiful- all spaces

With His all-regarding faces;

So He showed! If there should rise

Suddenly within the skies

Sunburst of a thousand suns

Flooding earth with beams undeemed-of,

Then might be that Holy One's

Majesty and radiance dreamed of!

This vision, as related in the eleventh chapter of

The Bhagavadgita (Edwin Arnold trans. 1885), is as beautiful as it is terrifying. Krishna, in his universal form, is all life and all death. This glimpse of a "

sunburst of a thousand suns" was famously evoked by Robert Oppenheimer at the Trinity atomic bomb testing on July 16th, 1945. Oppenheimer quotes Krishna from Chapter 11, Verse 32 (Wake fiends take note!) of the

Gita:

Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.

Once more, we witness a manifestation of Matter conjoined with Spirit to become pure Light. The

Vishvarupa, the Resurrection, the voice of the Thunder. The door briefly opened and yet still the heavens did not fall. Progress stomps on. Arjuna, like Achilles at Troy, is convinced by the gods to wage world-annihilating battle, bringing to a close the Bronze Age and ushering in the present iron age of Kali. The Trinity test is at once an echo and a foreshadowing. This age will also pass.

But history does not end. We drop out of it, one by one. We slip away from its nightmare. We bear true witness, even to horror. We at last heed the words of the Thunder: become generous, sympathetic, in self-control. Only with these do we exit the Chapel Perilous.

Chapel Perilous, like the mysterious entity called "I," cannot be

located in the space-time continuum; it is weightless, odorless,

tasteless and undetectable by ordinary instruments. Indeed, like the

Ego, it is even possible to deny that it is there. And yet, even more

like the Ego, once you are inside it, there doesn't seem to be any way

to ever get out again, until you suddenly discover that it has been

brought into existence by thought and does not exist outside thought. Everything you fear

is waiting with slavering jaws in Chapel Perilous, but if you are armed

with the wand of intuition, the cup of sympathy, the sword of reason,

and the pentacle of valor, you will find there (the legends say) the

Medicine of Metals, the Elixir of Life, the Philosopher's Stone, True

Wisdom and Perfect Happiness. -- Cosmic Trigger

In a collective sense, this is all of history. Everything we fear

and love is here. The events and rituals that perpetuate this

necessarily resound with the Thunder. All of this proceeds from the same creative power, the same Word, and so it has the ability to both fully awaken and to frighten back into sleep.

The

Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad, where Eliot's Thunder is summoned from, presents one of the earliest (c. 700 BCE) and most excessive accounts of hierogamic ritual. According to Mircea Eliade:

In the procreation ritual transmitted by the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad, the generative act becomes a hierogamy of cosmic proportions, mobilizing a whole group of gods.

In

Book 6 of this work, a husband (HCE) solemnly intones to his wife (ALP): "

I am heaven and you are earth."

The ceremony is about to begin:

Then he spreads apart her thighs, repeating the following mantra:

"Spread yourselves apart, Heaven and Earth."

Inserting

the member in her and joining mouth to mouth, he strokes her three

times from head to foot, repeating the following mantra:

"Let Vishnu

make the womb capable of bearing a son! Let Tvashtra shape the various

limbs of the child! Let Prajapati pour in the semen! Let Dhatra support

the embryo! O Sinivali, make her conceive; O goddess whose glory is

widespread, make her conceive! May the two Atvins, garlanded with

lotuses, support the embryo!"

Here it is one last time.

Inluminatio coitu. The grand finale: the rent veil, conception, birth, death,

vishvarupa, resurrection, singularity, nuclear blast and falling towers. The rains come, the long drought ends and the dragon is slain. Eliot signs off his

Four Quartets with a flash of the

Paradiso:

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flames are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.