The eye through which I see God is the same eye through which God sees me.

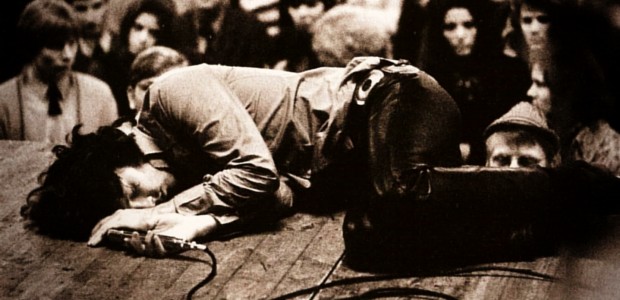

The 2006 DVD release of director Toshio Matsumoto's 1969 debut feature film, The Funeral Parade of Roses, has over the past few years generated a renewed fascination for this lost classic of Japanese new wave film. This film, in its presentation of the gay and psychedelic subcultures of late 1960s Tokyo and in its transgressive depictions of sex, violence, radical politics and avant-garde film-making, is truly a portal back to a very different era.

The film's supposed influence on Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange is by now almost common knowledge among lovers of strange films. The similarities in style and mood of the two films are immediately obvious. The sped up scenes accompanied by ironic music of fighting drag queens in Parade and ménage à trois sex in Clockwork, the rival gangs, the excessive lifestyles of the gay-boys and the droogs, have been noted and compared numerous times.

A less often explored comparison, though, is that of theme. An explicit source for Funeral Parade of Roses is the myth of Oedipus, specifically Sophocles' tragedy Oedipus Rex. In both the myth and the play Oedipus is destined to murder his father and marry his mother. Despite the best efforts of both Oedipus and his parents to avoid this fate the inevitable occurs. On finally discovering the truth his mother, Jocasta, commits suicide and Oedipus blinds himself.

This myth was the basis, of course, for what Freud called the Oedipus Complex, perhaps best summed up by the song "The End" by the Doors -- "Father -- yes, son -- I want to kill you, and Mother I want to rape you."

Eddie, the young transvestite protagonist played by real-life Shinjuku gay-bar dancer, Peter, in his debut on the big screen, is clearly Oedipus. And, at the slight risk of spoiling an unspoilable film, Funeral Parade is at first viewing an inversion of the classical myth -- Eddie kills his mother and sleeps with his father. When the truth is finally revealed the father kills himself and Eddie stabs in his own eyes.

In a closer viewing, though, we find that this inversion is only apparent. Eddie has flashbacks of his father abusing him as a child, and later abandoning he and his mother. When Eddie suggests to his mother that she forget her departed husband because she has him -- the classical Oedipal outcome -- his mother laughs in his face, causing deep trauma.

Later, when young Eddie finds his mother making love with another man, Eddie stabs and kills the man -- the surrogate father -- and then slays his mother, sitting on her supine body and stabbing downward in a manner clearly resembling rape. Leda, the mamma-san of the gay bar that Eddie much later becomes a hostess for, as his boss and as the lover of his actual father becomes his surrogate mother. Her own suicide, followed by that of his father and Eddie's own blinding, completes the mythic cycle.

A Clockwork Orange can also been seen as reworking of the myth of Oedipus. Alex, the film's anti-hero, takes on several father figures, perhaps because his own biological father is shown as being a weak and powerless man. This theme is even more explored in Anthony Burgess' original novel. The principle father figure is the writer F. Alexander who lets an abused Alex into his house, initially not knowing that Alex and his droogs had brutally raped his wife two years before, eventually leading to her death.

In the novel, Alexander is the author of a manuscript called "A Clockwork Orange" and so, in a sense, he is Anthony Burgess himself -- a writer whose own wife was beaten and raped by four American GI deserters during the war. Kubrick alludes to this connection by referring to an "Alex Burgess" in a brief shot of one of the newspapers announcing Alex's suicide attempt.

Both films centre on the eye. Alex's right eye is accentuated by false eyelashes, another visual motif that Kubrick directly borrows from Matsumoto. In fact, Matsumoto's short film, released immediately before Funeral Parade and using some of the same footage, is called For The Damaged Right Eye. Alex has stylized eyeballs on the cuffs of his shirt, the eye on the right featured prominently on the iconic movie poster.

In an interview, Toshio Matsumoto discusses his desire to transform perception in his films and in Funeral Parade of Roses most notably. He explains that all art, even the most subversive, eventually becomes formulated and co-opted into the system. He points out that even the law of perspective in painting is "an institutional system." It conditions the way that we perceive both art and the world, and it is now so commonplace that it is almost entirely unquestioned. The role of the real artist is to challenge and overthrow all such institutions of perception.

This extreme viewpoint was prominent in the late sixties, a period Matsumoto considers to be the most radical since the 1920s. The global student movement, radiating outward from Nanterre in Paris in May of '68, existentially challenged the political and social establishment. This in turn sparked off an even deeper revolutionary movement -- the desire to negate all forms of power, even those unexamined forms within our own act of perceiving the world and ourselves. He admits that during the making of Funeral Parade that his main concern was to "devour the system." In his own words:

Anyway, that's how I started to think. ... how to devour this system. As a political problem, the system is not only the power that oppresses people in this or that way or visible forms of political repression. Power is also what systematizes our thought, feelings, art, and culture in invisible ways. If we don't become aware of this and shake its foundations, we cannot move the structure of power in a real sense. That's why... we came to be controlled by more invisible things like human consciousness, feelings, points of view, or values. I thought that the most pressing issue facing art was how to become aware of this and work to undermine the system as a form of customary inertia. Films that startle and arouse self-awareness of that kind of internal distortion change the condition of cinema itself--this I think is art's form of struggle against authority.

In Matsumoto's view, power will eventually systematize all modes of thinking and perceiving. Art will always be absorbed and neutralized in this way, and sync of course is no exception to this. Art, if it is anything at all, is a continual process of de-systemization. It constantly challenges and overcomes the boundaries of perception. If it does not do this we are soon enslaved.

Funeral Parade of Roses challenges boundaries by breaking the so-called "fourth wall." The characters in the film reveal that they are simultaneously the subjects of a real-life documentary. In A Clockwork Orange, in the book more so than the movie, this wall is breached by having the book, A Clockwork Orange, itself appear in the narrative.

In a chapter in Burgess' book, Alex is able to read a section of Alexander's manuscript. Alexander describes here how people are as fruit hanging on a great tree of life planted and tended by God. In the modern era, though, God has withdrawn and human individuals are on the verge of becoming machines -- clockwork oranges. The true god, the original father, is absent from the world and we are now dominated by a different patriarchal authority -- scientific mechanization and the State and elite who profit from this system.

It's interesting that a similar point of view is expressed by the character of the Fool in a famous scene within Akira Kurosawa's 1985 epic film, Ran. The Fool is also played by Peter, in his most well-known role since Funeral Parade of Roses. On the battlefield, at the death of his master Hidetora -- Kurosawa's King Lear, Kyoami the fool laments that there are no gods or Buddha. He cries:

If you exist, hear me! You are mischievous and cruel. Are you so bored up there that you must crush us like ants? Is it such fun to see men weep?

The Fool is wise just as Oedipus' adviser, the blind Tiresias, was the only man who could truly see. We are all subject to the spiteful caprices of the god of this world. Manifesting as an evil destiny to Eddie and appearing as conservative or liberal representatives of the establishment to Alex, this appears to be the final father to slay.

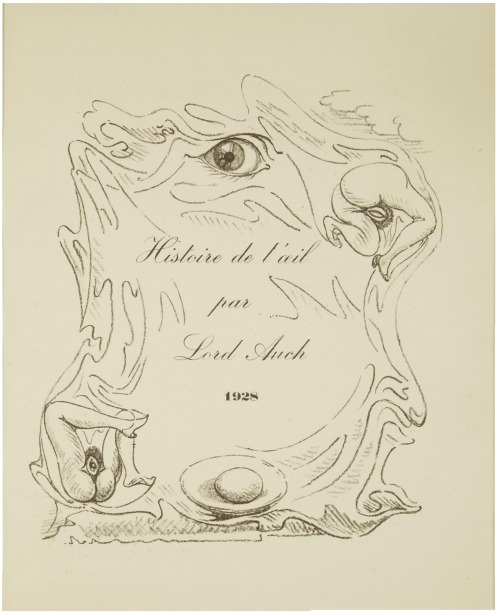

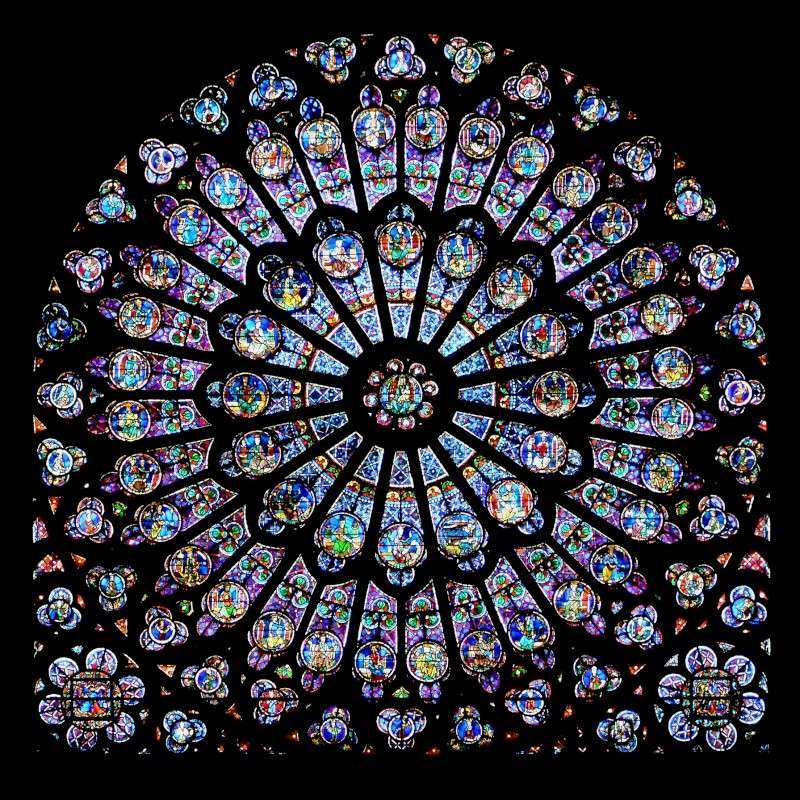

Georges Bataille's 1928 novella, The Story of the Eye, is a likely influence on both Funeral Parade and Clockwork. Its grotesque episodes of total transgression are in excess of those in both movies. The twenties were more radical than the sixties. The book's climax -- a violent orgy in a church involving the brutal murder of a priest and the use of his eyeball in the sexual rites -- aims at total sensory and conceptual liberation.

Bataille himself has a complex but direct link to the myth of Oedipus -- his father was blind at the time of Bataille's conception. He addresses this in his W.-C. Preface to Story of the Eye:

Since my father conceived me blind (absolutely blind), I cannot put out my own eyes like Oedipus. Like Oedipus I guessed the riddle: nobody guessed further than me.

Bataille, and The Story of the Eye in particular, went on to become a major influence on the generation of May '68 in France. Radical theorists, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, often cite Bataille as an influence and it was these two who launched a direct assault on Freud's doctrine of the Oedipus Complex.

In their seminal 1972 text, Anti-Oedipus, they assert that Freudian psychoanalysis, in its efforts to resolve the Oedipus Complex, is really only a tool by capitalism and the state to make the individual members of the nuclear family repress their own desires and conform to the organizing principles of society. The familial father is neutralized, but he is replaced by a much more powerful patriarch.

The titles of Funeral Parade of Roses and A Clockwork Orange hint at a repression and oppression that can only be called gnostic in its depth and malevolence. Both roses and oranges are solar symbols, and the Demiurge has always been identified with the Sun. A funeral parade (or funeral parades -- plurality is not indicated in Japanese) is a procession of death. A clockwork mechanism is similarly the endless unwinding of dead matter.

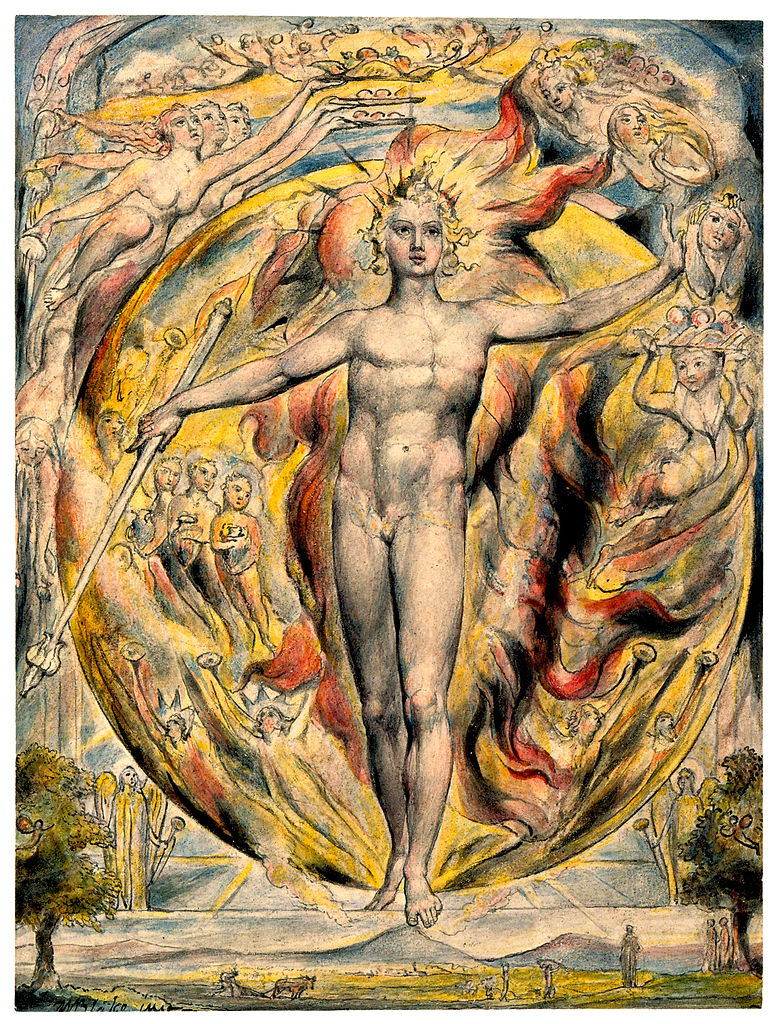

Neither the rose nor the orange, nor even the Sun are essentially negative images. Each contains vitality and joy of expression. The eye is also a symbol of the Sun. These symbols have all been co-opted by the system of control, but this does not need to be the case. Liberating symbols can again be liberated. William Blake in particular recognized this.

Blake wrote in his epic poem Jerusalem that:

A man's worst enemies are those

Of his own house & family.

Blake understood, like Deleuze and Guattari, like Bataille, and like Kubrick and Matsumoto, that the conformist, authoritarian, life-stifling will of society is most effectively brought down on the visionary artist by the close family. It is our parents, our siblings, our spouses, children and closest friends, not the police or government or other figures of authority, who most intimately pressure us to give up our wild dreams, to reign in and snuff out our creative imagination. It is the nuclear, Oedipal family that most limits our vision.

Blake called this limitation the single vision in contrast to the double vision of imagination. He most famously illustrated this with the image of the Sun. He wrote:

"When the sun rises, do you not see a round disc of fire somewhat like a guinea?" O no, no, I see an innumerable company of the heavenly host crying "Holy, Holy, Holy is the Lord God Almighty."

The prosaic, guinea Sun is what the Oedipal family, what the authoritarian State with its materialist ideology, wants us to see. To see anything else is to be, by definition, crazy. The doors of perception must be kept firmly closed. The power system is well aware that the only escape from the reign of clockwork, from the endless procession of funerals, is through the eye.

In the two films this escape does not appear to have happened. Certainly in A Clockwork Orange it does not. Alex's eyes are wide open to the violence of this world but they are blind to any deeper vision. He becomes an agent and a pawn of the same authoritarian State that tormented him. He remains a slave to the god of this world. In general, Kubrick appears to portray the establishment forces as being supreme. Despite its surface transgression, there is no liberation in A Clockwork Orange.

Funeral Parade of Roses is more promising. The hope and possibility of liberation is present throughout the movie. It is subversive while A Clockwork Orange is reactionary. Eddie blinds himself in the end, but does he, like Oedipus eventually, come to see a higher vision? Does his blindness, like that of Oedipus, finally end the cycle?

The tale of Oedipus is not even unique in Greek myth. The same story is ubiquitous. The primal god, Uranus, is castrated by his son Kronos or Saturn, who in turn is overthrown by his son Zeus or Jupiter. In every case, it is the mother goddess who spurs on her son to bring down his father. The controlling system is really Oedipal and not exclusively patriarchal. The mother, like Eddie's mother in Funeral Parade, laughs in our faces, causes us to doubt our virility, traumatizes us.

The myth seems to change, though, with the present Archon. Jupiter is Jove or Jehovah and his son is Christ. Christ rejects the world represented by his mother, but he also uniquely declares that "I and my Father are one." The Oedipal cycle is finally overturned. It does not continue. It is finished. Only its illusion remains, and illusion is what double vision dissipates. We already possess the father's kingdom within. In contrast, to have eyes wide open in this world, as sightless Tiresias attempted to teach Oedipus, is to be truly blind.

Blake is a Christian gnostic anarchist. Toshio Matsumoto is also in a certain sense. We do not need, of course, to slay or reject or even resent our families in order to free our imagination. To do so, in fact, only perpetuates this system of control, this nightmare of history. We do need, as Matsumoto, Blake, Bataille and so many others revealed, to open all the doors of perception. These visionaries, appearing as blind or crazy to the world, are those who can teach us to truly see.

All definitions of cinema have been erased. All doors are now open.

-- Jonas Mekas (as quoted in Funeral Parade of Roses)

Harsh reality for sure . Thank you for this vision. Dennis

ReplyDeleteThanks, Dennis. Harsh and beautiful at the same time.

DeleteI agree that Kubrick's vision is narrow and reactionary - glad someone else noticed! (Tho Pauline Kael did in her review of the film.)

ReplyDeleteI think it's true of all his later movies. SK was a square "genius" - which has to be an oxymoron, surely?

Great to see you on here, Jasun.

DeleteYes, maybe 2001 offered a glimpse of transcendence, but all of his later films keep us deeply mired in the "world of shit."

Ah, Full Metal Jacket. Probably one of my favorite Kubrick movies... Another great essay, BTW. Really enjoying your blog & thanks for linking me up on your blog roll!

DeleteSnow White is a Japanese ladyboy. She who wields the dagger blinds her physical eyes in the Father's suicide. Deactivation of HAL's oz iris. Danny with the dart board on the bull's eye. In a Biblical inversion, the Mother (Sarah) laughs when the Son (Jacob) asks of his Father (Isaac). Jacob cuts the Mother to pieces, but redeems himself by becoming Rachel and recovering the androgynous image.

ReplyDeleteI disagree with your assessment of A Clockwork Orange. Alex traverses the full sequence of the Tarot and by all right has been granted an apotheosis, as I have written.

Wow. What a fantastic analysis. Thanks for pointing me to it. All that as a given, I still have a bleak outlook on the film. It seems to map out a false initiation. Perhaps the reflection of 2001. Perhaps not.

Delete"The rulers of the world now tremble before him, and he has become a King among men."

I just don't see this as being the case. Alex becomes an even more effective pawn than he was before. Kubrick's elimination of Burgess' final, "positive" chapter seems to confirm this.

The final chapter was jettisoned because it had no esoteric significance. There are subtle changes all throughout the work that underscores that Kubrick has turned Burgess' nihilism into optimism. Rob Ager has noted much of this. Note the alterations to the final scene vis-a-vis the book.

DeleteAlex is Stanley Kubrick. The government man is the Empire that uses his work (cinema) for entertainment purposes. ("Alex, you can be instrumental in changing the public verdict.") By making films, he will be "helping" the multitude fixate on exterior illusions. But Alex is cunning; he can use their tool against them in the pursuit of something transcendent, and thus keeps his eyes focused on the spiritual ideal by looking to the light above.

This is conformable to Joseph Campbell's Monomyth. The hero must embody two worlds, the physical and spiritual. The Outer Church persists for as long as the residents of Plato's Cave continue to be entranced by the shadows on the wall of the movie theater. The philosopher will glimpse the intelligibles, but must also descend back into the darkness.

"... the philosophers of the Platonic school and those of the Neoplatonic favored the idea that Homer's blindness was symbolical, that it indicated not his inability to see on the objective level but that he had voluntarily turned his sight inward, to the contemplation of those things normally invisible."

Publicly, at least, Kubrick rejected the last chapter because it seemed to him "unconvincing and inconsistent with the style and intent of the book." Whether or not Kubrick had any deeper reasons for leaving it out, Burgess clearly found it to be crucial.

DeleteIt DOES have esoteric significance. In it, Alex discovers his Free Will. He decides to fully reject his previous sociopathic behavior. He ceases, in Burgess' original sense, to be a clockwork orange -- a mechanized, manipulated organism. Free will enabled the Fall and free will must also be the basis for Redemption. The entire esoteric system of Dante, etc. is centred on this.

In the book Alex has fallen even further than in the movie (the two teenage girls he consensually has sex with in the movie are in the book 10-year-old girls he rapes, Alex kills a man in prison, etc.), and yet he is still redeemed. Without the 21st chapter there is no Universe, no real resolution (his final daydream is unsatisfying in this regard).

Even after reading Ager (and thanks for directing me to his work), I remain unconvinced that in the movie Alex has any intention of betraying the government and still less of helping any one else but himself. The government knows this and they will exploit his self-serving, sociopathic tendencies to the fullest. Both gain from this relationship.

Alex certainly suspects that he is still being manipulated. His question to the government psychiatrist confirms this:

ALEX

Well, when I was all like ashamed up and half awake and unconscious like, I kept having this dream like all these doctors were playing around with me gulliver. You know... like the inside of me brain. I seemed to have this dream over and over again. D'you think it means anything?

DR. TAYLOR

Patients who've sustained the kind of injuries you have often have dreams of this sort. It's all part of the recovery process.

ALEX

Oh.

There is no reason for us, as Ager suggests, to believe the psychiatrist and to take this as part of Alex's hallucinations. There are plenty of reasons to believe that Alex was aware of something that actually happened to him. But regardless of the truth, which we will never discover, Alex clearly is suspicious that he has been altered against his will in some way.

I am not denying that there is an esoteric or alchemical layer to this film. Your post should convince anyone that this level exists. But something big is missing. The humanistic, redemptive conclusion is absent.

An uninitiated person can enter a cathedral, witness a great piece of art or music, or even watch a film like 2001 and experience a sense of awe in the end. He may not understand what he sees, but he can feel its power. The same person will likely be left feeling uneasy after watching ACO, even if at the same time he acknowledges it as a work of genius. The epic is unfinished and on some level we all sense this.

So, yes this esoteric layer is there. I also agree with your comments on Campbell but perhaps from the reverse perspective. Even if we are to conclude that Alex did achieve a sort of spiritual transcendence, then it is still difficult to accept that any physical liberation took place. And without the latter the former rings hollow. As in Blake, final revelation emerges out of revolution, and successful revolution is only possible when it leads to revelation. Yeats' desire "to hold in a single thought reality and justice" amounts to a similar idea.

It may be that Kubrick aims ultimately to get us to look beyond the shadow-play, and with enough effort and insight we CAN find the light shining in everything, but there is little suggestion that we knock down the walls of the cave. Matsumoto encourages both. So do I.